Greetings to the ladies of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated.

Greetings to the ladies of Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Incorporated.

Greetings to the ladies of Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority, Incorporated.

Greetings to the men of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Incorporated.

Greetings to the men of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Incorporated.

Greetings to the men of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Incorporated.

Greetings to the men of Iota Phi Theta Fraternity, Incorporated.

Greetings to the “Sons of Blood and Thunder,” the men of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Incorporated.

And my warmest greetings to my Sorors,

the Dynamic Divas who wear the Delta symbol, the ladies of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Incorporated.

It is my pleasure to offer you an introduction to the nine Black Greek-Lettered Organizations (BGLO), dubbed the “Divine Nine.” These black fraternal groups first emerged shortly after the turn of the twentieth century to help black college students, who W.E.B. Du Du Bois famously dubbed the Talented Tenth survive the racially hostile environment of daily life as blacks in America which even educated, middle and professional class blacks could not escape.

By May 1930, Omega Psi Phi and Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternities and Alpha Kappa Alpha, Delta Sigma Theta and Zeta Phi Beta Sororities recognized the need for “unanimity of thought and action” among Black Greek letter organizations. These organizations served as the charter members of the National Pan-Hellenic Council and were joined the following year by Alpha Phi Alpha and Phi Beta Sigma Fraternities. Sigma Gamma Rho joined in 1937 and Iota Phi Theta Fraternity completed the list of member organizations in 1997.

I’ve set my sights on a noble but admittedly lesser goal of introducing to some and presenting for reexamination to others, a few of the most popularly shared practices of Black Greek-Lettered Organizations. It is not intended to be definitive in nature. Instead, it explores the history, application and transformation of some of the most beloved traditions in the black fraternal experience.

Believe it or not we’ve already shared one of the Divine Nine community’s most beloved traditions, that of the call. At any public gathering of BGLO members, it is not uncommon to hear vocal utterances, either words or sounds. These calls are not only coined for use by their respective organizations, but distinctive to each BGLO affiliation. Its common usage is in the call-and-response style so familiar with the African-American church tradition. Similarly, a call is begun by one member or members who are joined by other members with the same or a responding call.

The origins of these calls however, stretch back to the continent of Africa where, calls were used to communicate one’s location most often over long distances. Once enslaved in the Americas, Africans continued to use their call-and-response traditions to communicate with each other, protect themselves from danger and to express emotion. In the fields, they’d often sing out in songs in the call-and-response tradition to ease the pain associated with the harsh labor conditions they endured, while carrying out their daily tasks. But once slavery ended, it diminished the value of call-and-response tradition in the everyday black experience and northern blacks often looked at the tradition with scorn. The same is true of some BGLO members, who frown on the practice of calls, since they are “unofficial” practices in some Black Greek-Lettered Organizations. Like hand signs, whether official or unofficial, calls serve as an integral part of the black fraternal experience and as such should not be used by non-members to fake membership. It is not only looked at unfavorably, but it viewed as an affront to BGLO members.

Just as calls have their origin on the continent of Africa, the practice of branding, most popular among black Greek letter fraternities, are purported to have roots in African scarification rituals. Others claim that the practice is connected to cattle branding and slavery; and others still, claim that the practice was popularized during times of war as a means to identify the bodies of black servicemen. And herein lies the paradox of the ritual. As a practice often unrecognized by BGLO national governing bodies, branding, while widely practiced by some, is scorned by others, leading to a general lack of consensus about its function in the black fraternal community. But as Marcella L. McCoy observed, “a ritual is an act to which someone gives meaning, emotion, and order but that may seem insignificant to others.”

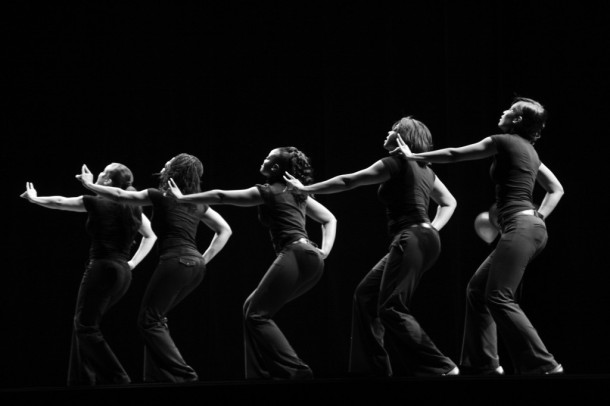

One shared ritual over which there is little debate is the syncopated, percussive rhythms that emerge from the marriage of precise and stylized movements of the body capture the audio and visual imaginations of observers. This art is dubbed stepping. “Frequently coupled with songs, chants, and verbal calls,” Carol D. Branch describes stepping as “a vibrant performance that has been shaped by the experiences of blacks, yet continues to evolve.” Generally performed in groups, stepping helps maintain the social cohesiveness of the black fraternal community. The practice’s origins are also African, and can boast roots in the call-and-response tradition as well as in games played by Congo children and in the gum-boot dancers of South African mines. Historians of Phi Beta Sigma contend that its member Kwame Nkrumah, first prime and later president of Ghana, introduced the heavy West African influence on BGLO stepping as well as the cane, although I am certain that the men of Kappa Alpha Psi would invite a healthy debate over the introduction of the cane to the black fraternal tradition.

It is difficult, if not impossible however, to draw a straight line from African traditions to supposed manifestations in black fraternal life. Yet, as Alpha Phi Alpha member W.E.B. Du Bois in his 1908 publication The Negro Family, pointedly asserted:

“In each case an attempt has been made to connect present conditions with the African past. This is not because Negro Americans are Africans, or can trace an unbroken social history from Africa, but because there is a distinct nexus between Africa and America, through broken and perverted, is nevertheless not to be neglected.”

The powerful African symbolism behind the circle is something upon which all BGLOs agree. In Africa, the circle dance predominated everywhere, sometimes with solo dancers or musicians in the middle, other times with couples and was an essential element of both religious and secular ceremonial dancing. When viewed in a broader context, the anthropological influence of the circle as representative of consistency, continuity and endurance as most commonly displayed in the exchange of wedding rings during marriage ceremonies, also lends the symbol to uses in the black fraternal tradition. Hence any circle of BGLO members should, as Marcella McCoy observed, “never be broken and all those who wish to pass must walk around the circle.” This deference is also extended to the stroll, which is an extension of the circle, and similarly, should never be broken by non-members.

Believe it or not, stepping and step shows were not always a part of the black fraternal tradition. Most older members of BGLOs readily acknowledge that the present incarnation of stepping is a rather recent phenomenon in the long history of black fraternal life. Up until the 1940s and 1950s, stepping was virtually unheard of.

Fisk University librarian and William and Camille Cosby Professor Dr. Jessie Carney Smith, who was initiated into Alpha Kappa Alpha at North Carolina A & T during the 1940s, said that there was no stepping among BGLOs during her time in undergrad. Her first encounter with the emerging tradition was viewing the Omega men of Marching Eta Psi, after she joined the staff at Fisk University during the 1950s. Similarly Dr. Frederick Humphries, former president of Tennessee State and Florida A & M universities, who pledged Alpha Phi Alpha during the 1950s at Florida A & M, recalled that he never stepped. In jest, he said, “We were too dignified to step. We stuck to recitations, poetry and serenades.” Mrs. Barbara Murrell, who was initiated into Delta Sigma Theta at Tennessee State during the 1950s likewise recalled, “We did march in line to the center of campus, but what we did was perform things more akin to little ditties—you know, cute stuff.”

![]() What we can be sure of, is that the explosive popularization of stepping in its modern day form, is owed to Spike Lee’s 1988 cult classic School Daze. Likewise, its performance as a part of the 1996 Olympic Games opening pageant catapulted the practice to global fame. Today, the ever-growing popularity of the art-form is evident in movies, music videos and even, exercise videos. The nation’s attention was drawn to stepping during the Sprite Step Off in Atlanta, Georgia in February 2010. But when the all-white Zeta Tau Alpha team from the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville won the competition (which was later changed to a first-place tie with Indiana University’s Alpha Kappa Alpha chapter), heated debates ensued between supporters and detractors of the white Zeta’s undoubtedly masterful performance over supposed cultural theft.

What we can be sure of, is that the explosive popularization of stepping in its modern day form, is owed to Spike Lee’s 1988 cult classic School Daze. Likewise, its performance as a part of the 1996 Olympic Games opening pageant catapulted the practice to global fame. Today, the ever-growing popularity of the art-form is evident in movies, music videos and even, exercise videos. The nation’s attention was drawn to stepping during the Sprite Step Off in Atlanta, Georgia in February 2010. But when the all-white Zeta Tau Alpha team from the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville won the competition (which was later changed to a first-place tie with Indiana University’s Alpha Kappa Alpha chapter), heated debates ensued between supporters and detractors of the white Zeta’s undoubtedly masterful performance over supposed cultural theft.

What followed in its wake, were accusations of reverse racism as well as race-based taunting and name-calling. Now, placed within the broader context of black fraternal traditions, members of the BGLO-community can readily acknowledge that good-natured and sometimes, not-so-good-natured taunts have long been par for the course. Most recently, a video surfaced featuring Virginia Tech’s Farmhouse, a white fraternity, as the winners of the institution’s Greek Unity stroll-off, reigniting debates over mimicry and cultural appropriation.

That being said, what we must address now is the question, “Who owns these traditions?” And does the spread of them to non-black fraternal life amount to cultural theft any more than the spirituals, jazz, the three-part gospel harmony, rhythm and blues or hip-hop?

There is, however, another on-going debate surrounding BGLOs, that I’d like to address before closing. Recently, the secret nature of black sorority and fraternity rituals have come under attack by a small sect of members and some non-members, who have characterized by them as being ungodly. Such characterizations are not only inaccurate but also stem from what Charles S. Finch III recognized as the “certain tendency in modern Western culture to disparage and dismiss the values and customs of the past [and] to view with condescension and scorn the lifeways, practices, and cultural perspectives of ancient and traditional peoples. Passwords, secret knowledge, symbols, peer group bonds and lifelong relationships of mutual support,” noted Finch, “all reflect sociocultural institutions whose origins are discernible in the dim mists of antiquity.” For it is precisely the open nature of their secrets which make these fraternal groups so attractive to nonmembers. As Mary H. Nooter keenly noted, “To own secret language, and to show that one does, is a form of power.”

The degree to which Black Greek -Lettered Organizations have power, and are able to harness their power to positively impact college campuses, communities, the nation and world, lies within the willingness of the black fraternal community to constantly assess and reassess themselves. Leading this charge, are the respective national governing bodies of BGLOs, which is in part, why it is necessary for members to remain personally, ideologically and financial connected with their respective fraternal organizations. Black lives must matter to us.

The truth of the matter is that while the popularity of stepping may make it seem as though black Greekdom is “steppin’ to survive,” BGLOs must negotiate the more treacherous waters surrounding things such as rites of passage as well as “unofficial” rituals if black fraternal life is to thrive in the 21st century. As a community, we must decide whether our futures must look exactly like our pasts, in order to keep alive the dreams of our founders. Collectively, we must recommit ourselves to our most scared tenets and continue to share the mantle of fraternity and collective responsibility, through scholarship and service. These are the aspects of black fraternal life which are central to BGLO history and while they have not been captured by popular culture, these are the traditions that are most important as we step into the future.

A member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., Crystal A. deGregory, Ph.D. is a graduate of the historic Fisk University ’03. She received her master’s and doctoral degrees in history from Vanderbilt University. She also holds a master of education degree in curriculum and instruction from Tennessee State University, ’14, where she formerly taught in the department of history, geography and political science. A professional historian and passionate HBCU advocate, she is editor-in-chief of the forthcoming The Journal of HBCU Research + Culture. She is also a regular contributor to HBCU Digest, is a co-host of Black Docs radio show, and offers a wide-range of expertise on multiple topics including history, culture, education, black fraternity and sorority life and of course HBCUs. Follow her on twitter at @HBCUstorian, visit her website at www.CrystaldeGregory.com, or contact her via email at cadegregory@HBCUstory.com.

A member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., Crystal A. deGregory, Ph.D. is a graduate of the historic Fisk University ’03. She received her master’s and doctoral degrees in history from Vanderbilt University. She also holds a master of education degree in curriculum and instruction from Tennessee State University, ’14, where she formerly taught in the department of history, geography and political science. A professional historian and passionate HBCU advocate, she is editor-in-chief of the forthcoming The Journal of HBCU Research + Culture. She is also a regular contributor to HBCU Digest, is a co-host of Black Docs radio show, and offers a wide-range of expertise on multiple topics including history, culture, education, black fraternity and sorority life and of course HBCUs. Follow her on twitter at @HBCUstorian, visit her website at www.CrystaldeGregory.com, or contact her via email at cadegregory@HBCUstory.com.

Reblogged this on justdeeblog.

Excellent commentary Soror and this will be disseminated widely to educate and inform. Thank you and be blessed!! RQQ-OOP!!!!

RQQ!

Awesome information, Thank-you for sharing..Soror!

AOML.

This is a wonderful explanation of the history behind it all. Our purposes and pieces of our history are becoming more and more convoluted as time progresses. Thank you on behalf of some of our youngsters for the history lesson and for the reminder to this of us who may have forgotten.

Indeed, we have to make certain that they are as captivated with the reasons for which we step as they are with stepping.

As recently as 1980 at Morgan, Howard, & Hampton they were still called Greek Sings, not Step Shows. Equal parts serenading, and stepping.

I really appreciate your comment. Respect!

Thanks for reading and commenting Jimmy. Respect!

Thanks for reading and commenting! I’m not surprised by that at all. We’ve got to get these histories down on paper + quick.

Nice article, but the first organization to put on a “STEP SHOW” was Groove Phi Groove social fellowship inc.

Dear Diamond,

Thanks for reading and commenting. I invite you to make such definitive contributions with sources if possible–we’d certainly publish it.

Dr. de

This was WELL WRITTEN & VERY KNOWLEDGABLE!!! Thank you for sharing this!!!

Thanks for reading and commenting Tracey!

Thank you for sharing the history of BGLO. These organizations are still very important today, as in the time of W.E.B. Dubois,to represent Afro-American college and university graduates;because achieving the highest degrees from the finest institutions of learning, still does not guarantee respect or escape from racism.

As Afro-Americans in this nation, we need to forever step and drum the importance of education, so that our people can discern and especially comprehend the many forms and appearances of racism in our communities. Black lives, Afro-Americans lives do matter!!!

“Drum the importance of education.” Yes, I love that! Thanks for reading and commenting.

Reblogged this on urban philosopher.

The hop was first done with perfection at Tennessee State University, an ROTC student on line for Omega Psi Phi “Mighty” Rho Psi Chapter combined words and a military style March to create the first hop. This was in the early 50’s as your time line indicates. Stepping is different from hopping and not practiced by Omega’s, however hopping was the origin of this practice among greek letter organizations.

Dear Martez,

I received similar claims from members of the Omega’s Eta Psi chapter at Fisk, from much older members than you. I thought it important to begin a substantive conversation about BGLO traditions as a reminder that they have history meaning and should continue to have contemporary value. I invite you to make such definitive contributions with sources if possible–we’d certainly publish it–as well as the specificity of “hopping” as an form separate and apart from “stepping.”

Dr. de

Thank you for sharing your knowledge.

Thank you for reading and commenting Denise!

Hi Soror,

My dissertation research on brands, calls and stepping was so illuminating (and fun) collecting and documenting the stories from members initiated As early as 1940.

Thanks for the conversation!

Marcella McCoy-Deh

Soror McCoy-Deh,

With all the recent talk about who can and can’t step, I thought it important to pivot the conversation and talk some about why we step. There are many important BGLO traditions that are misunderstood even by BGLO members. Thanks for your work [which I referenced] and eternal thanks to our founders, we can [as the Baptists would say] return to the “Old Landmark.”

YID!

Awesome read. Interested in reading more. Way to work

I am truly enlightened by reading your thoughts. They are certainly applicable to my own life, as I began stepping in high school for Dem Raider Boyz Step Squad, followed by stepping for my freshman year dormitory at Howard University, and ultimately served as the Step Master of my beloved Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Alpha Chapter.

Here’s the catch: I’m an Indian American.

I can recall my father many years ago (when I first tried out for my high school step team) ridiculing my interest, as this was an art “not of our culture”.

Many years and many step shows later, I find myself as a middle school teacher in an urban middle school in southwest Houston empowering my students through the art of stepping. While some may see me as a part of this “cultural theft”, it has become an important part of my own personal identity and culture.

Thanks again for such a thought-provoking piece.

I think this article was amazing. I enjoyed reading every word of this. It was more then informative but it makes me ant to be apart of my sorority of choice even more. Knowing where the heritage comes from and the things it represents. The call and the circle that they all perform I never knew this history behind these things. Knowing the dates and how the “Talented tenth” and “Devine nine” stood for is amazing all in its own.

honestly helped so much !! then i scroll down and see a member of Delta Sigma Theta i love you ladies !!!! just wonderful helped so much with my mid term paper